|

The very sad state of Tea gardens in West Bengal

the link

A link below FYI

http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/13-years-too-late-for-many-in-north-bengals-tea-gardens/

Maria Goretti Soreng can only walk now with the help of a walking stick that towers over her frail 5-ft frame. There are strands of white in her hair that weren’t there two months ago. Her legs are swollen like drums and she runs a fever most of the time. Maria is 38.

Her husband Dominique Soreng, 54, has rashes all over his body. His stomach is round and distended. He has long known what it’s to feel week, Dominique says. “But this (the rashes, the stomach swelling up) happened barely two

months ago.”

Maria Soreng, 38, has greyed and can’t walk without a stick anymore, husband Dominique has rashes all over his body (Express Photo by Partha Paul) Maria Soreng, 38, has greyed and can’t walk without a stick anymore, husband Dominique has rashes all over his body (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

Since May 17, the Duncans tea factory at Dhumchipara in Alipurduar district of North Bengal, where Dominique works, has been “more or less” shut. Dried tea leaves lie strewn on sorting tables and a sturdy lock hangs on the door of the processing shed.

In the past month, beginning October 13, nine employees of the factory and the Dhumchipara tea garden have died. Bagrakote — where reports of hunger deaths at tea gardens since it partially shut down in March prompted a visit by Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee to the region — saw casualties mostly among the ageing. Here in Dhumchipara, the youngest to die was 36-year-old Chanchal Mangar.

After Mamata’s visit, the state government announced a relief package promising food and water supply to tea workers.

The workers at Bagrakote, also owned by Duncans, got paid more too, Rs 122.50 a day. Dominique, who like most tea garden employees has worked on the plantation all his life — like his father and father’s father before him — got Rs 98 a day for eight hours of work.

Ratan Chettri of the Dooars Chai Bagan Workers’ Union says they have not been paid since February. “There are many workers whose condition is really bad — they are really at the threshold of death,” he says.

Dhumchipara Tea Garden in Alipurduar district

Established in 1907

Practically shut since May

9 deaths since October 13

Once the Dhumchipara tea garden produced 13 lakh kg of tea annually and had 3,400 workers. More than half, 1,400, have migrated — to Siliguri, Delhi, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Bhutan and mostly to Kerala.

According to law, each tea garden worker must receive, apart from their daily wages, provident fund payments, bonuses, pension (for retired workers), ration, umbrellas and aprons for working, firewood for cooking, housing, electricity, water, medical care and education facilities. The last time the workers got ration in Dhumchipara was in 2011.

The Adivasi colony (the other big community is of those of Nepalese origin) is the worst hit. There is no food at the Soreng home. Dominqiue’s brother and sister-in-law, also tea workers, have started working as stone collectors for construction contractors at a nearby river. Dominique says he and Maria eat when the two send over food — generally roti dipped in salty tea.

Dukhni of Dhumchipara tea estate, all of 30, is a skeleton now and unable to move; (right) husband Pradeep with one of their three children, Ayan. Showing the fistful of rice they have left, he breaks down, “Dukhni is unlikely to survive” (Express Photo by Partha Paul) Dukhni of Dhumchipara tea estate, all of 30, is a skeleton now and unable to move; (right) husband Pradeep with one of their three children, Ayan. Showing the fistful of rice they have left, he breaks down, “Dukhni is unlikely to survive” (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

Dukhni, 30, has three children — a girl (10) and two boys (5, 3). Reduced to a skeleton and barely able to move, she watches as husband Pradeep puts their evening meal together with all that is left — a handful of rice and four potatoes. Suddenly, Pradeep breaks down, “Dukhni is unlikely to survive. Doctors say she needs two packets of blood, but we don’t have the money.”

Other workers at the colony scrounge in the undergrowth of the tea garden and the forests beyond for food. Tea flowers are collected and scrambled into a sabzi as are edible roots and leaves.

Whatever that could be sold has been sold — cycles, goats, utensils.

Hemlata Beck, who is carrying tea flowers for that day’s meal, says sometimes they don’t even have oil to make a vegetable. “We simply eat the boiled shoots and roots.”

Beck is among the luckier ones. She and her sister travel four hours daily to Lakhipara tea garden, which is partially open, where they work as tea pluckers.

A survey by the Siliguri Welfare Association in July last year found the body mass index of tea workers to be as low as 14 in some estates. “The WHO has stipulated that anything less than 18.5 BMI constitutes famine-affected population,” says Abhijit Majumdar, secretary of the organisation.

Out of 1,272 workers at Raipur Tea Garden in Jalpaiguri, 539 or 42 per cent had a BMI of less than 18.5. As many as 384 workers had a BMI of 17, 285 below 16, and 140 less than 14. Similar surveys were conducted at Red Bank, Bandapani, Diana and Kathalguri tea gardens and same results found, says Majumdar.

2002 onwards, when the gardens started shutting down, there have been reports of hunger deaths. Workers say there is no warning, no suspension of work, no lockout; the management simply gets up and leaves.

At Kathalguri, the first tea estate to shut down in 2002, as many as 525 workers and dependents were reported to have died over the next three years. Between then and 2007, when 17 tea gardens shut down, human rights groups recorded at least 1,200 deaths in the area.

“Things are very bad,” says acting manager of Dhumchipara estate Vishank Singh Rathore. The senior management left one day making him in charge. “Whenever we ask the company what is going on, the head office tells us there is no money. There is no ration, no water. My own staff has run away… I have not been paid for seven months.”

Five nearby gardens also owned by Duncans, once one of the largest corporate houses in Bengal, are in a similar state, adds Rathore.

With the 630-hectare Dhumchipara garden deserted, theft from teak and Sal trees for timber is also rampant.

Recently, an ‘operating management committee’ was set up. “It picks leaves and sells it to factories still operating — we call this cash plucking. That’s how we have survived,” says Rathore.

The operating committee comprises the remaining staff of a garden, the trade unions and workers. The workers prune the tea plants and pick the leaves. For every kilogram they pick, they are given Rs 5 by the staff, which sells the leaves to a buyer for Rs 14-Rs 15 per kg. The buyer then takes it to his own factory for processing.

Bandapani Tea Garden in Jalpaiguri district

Established in 1895

Shut since July 2013

32 deaths in 2 years

“Between 2013-15, as many as 15 people have died in one labour line (a labour colony) here. And that’s just one labour line,” says tea garden worker Raju Thapa. “Thirty-two workers have died and we haven’t even counted the number of dead non-workers.”

The 1,000-hectare estate employs 1,667 people, apart from hundreds of their dependents. Once it used to produce 6 lakh kg of tea annually.

Ratiya Khariya, 45, was just “skin and bones” when he died last year, says wife Saniaro Khariya. “There was nothing left of him.” Both used to work as tea pluckers at Bandapani.

“There was no food in the house. Our three children were our priority. We would eat rice in starch water and salt. After a year of this, he just died,” says Saniaro.

Chandri Bara, whose daughter Hemanti went missing 8 years ago from Bandapani . Trafficking of women and children is believed to be rampant at the tea garden (Express Photo by Partha Paul) Chandri Bara, whose daughter Hemanti went missing 8 years ago from Bandapani . Trafficking of women and children is believed to be rampant at the tea garden (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

A survey by the Dooars Jagron organisation earlier this year found 74.04 per cent of the children at tea estates suffering from malnutrition. Victor Bose of the organisation, which works for rights of tea workers, says they also found rampant child and woman trafficking at Bandapani.

“Most of those trafficked are 12-15 years old. The two most common destinations are Delhi and Sikkim. They are taken as domestic help and exploited. The girls are handed over to the sex trade,” says Bose.

Chandri Bara’s 14-year-old daughter disappeared eight years ago, when things had already started going bad. She hasn’t been seen or heard from since.

Sital Munda, 45, of Bandapani tea garden, now makes a living collecting stones from river banks. A whole day’s pile gets her Rs 50 (Express Photo by Partha Paul) Sital Munda, 45, of Bandapani tea garden, now makes a living collecting stones from river banks. A whole day’s pile gets her Rs 50 (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

Sital Munda, 45, makes do by collecting stones from the banks of the Khakhra and Dhumsi rivers, metres away from the Bhutan border, as do her son and daughter-in-law. Sital has been doing this for three years. The river is mostly an expanse of rocks, rubble and sand, with water only during monsoon. For a pile of stones measuring 3 feet by 3 feet, she earns Rs 50 a day. Most days she only manages a pile.

The workers are now running a part of the tea estate through cash plucking.

The Kathalguri estate that has opened again uses MNREGS funds to pay for hundred days of tea-picking. Workers are hired for only half the month to slash costs.

Thapa blames the demise of the Bandapani estate on the management. Originally owned by the Darjeeling Dooars Plantation Limited (DDPL), Bandapani was first sold to Mohta Enterprises, and then to Sarada Pleasure and Adventure Limited, a Siliguri-based hotel.

“The last owner had no experience in running a tea garden. So he wound up after one and a half years. He used to run a chit fund, hundreds invested in that. We estimate lakhs of rupees were collected and the workers never got it back,” says Thapa.

After Thapa and others met the Jalpaiguri district magistrate, an investigation found that land deeds were never transferred and that, on paper, DDPL were still Bandapani’s owners. The state government took over the garden in September 2014.

However, despite some funds extended by the government, reviving Bandapani is an uphill task. There’s Rs 3 crore pending in workers’ provident funds and Rs 2 crore in gratuity. Another Rs 80 lakh remains due in salary arrears. Only recently, after a battle, pension was secured for retired estate workers, but it is just for just those belonging to Scheduled Tribes. The large Nepali population has been left out.

There is another side to the labour story. Tea gardens in North Bengal are regulated by the Tea Authority of India under the Plantation Labour Act, 1951, which oversees labour laws and ensures labour benefits, and the Tea Act of 1953, which deals with the functioning of the estate, the management, production, yield etc.

In recent years, as tea estates go to seed, small growers have flooded the area. While 10.12 hectares is the minimum requirement for setting up a tea estate, the small growers start plantations on fields as tiny as several acres.

This has led to problems, says United Trade Union Congress secretary Ashok Ghosh, who has written several papers on Bengal’s tea industry. While tea estates have to follow industrial laws, small tea growers operate under agricultural land use, and since they do not fall under the Tea Board, cannot be held accountable.

Since the government got involved at Bandapani, self-help groups are offering families living in abject poverty a cooked meal a day. The children at the garden get food under the ICDS.

Bandapani residents recently also got themselves a water supply. They collected money, laid pipelines and are sourcing water from Bhutan.

Bagrakote Tea Garden in Jalpaiguri district

Established in 1876

Shut since July

25 deaths since April

Since April, the 1,000-hectare Bagrakote estate has seen 25 deaths — six of them in the week between October 25 and November 1. It was this spate of deaths that led to an uproar and brought Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee here.

The Duncans management owes workers salary since March, 114 weeks of ration and over Rs 3 lakh in provident funds. Half of Bagrakote’s 2,976 workers have left for other states. Most of the tea plantation is now a jungle, with unpruned tea plants growing up to 10 feet.

Pavan Pradhan of the Cha Bagaan Mazdoor Union says there was never any official shut-down. “In March, workers and staff stopped getting wages… The tea pickers kept working as did the staff. One day we heard the managers had disappeared… This was around July, that’s when the work completely stopped,” he says.

Later, ration stopped, electricity and water supply was disconnected, the hospital shut down, and the theft of timber started. “Finally the management let us set up an operating committee,” says Pradhan.

Duncans Industries, that used to win awards for highest yields from the Tea Board in the late eighties, owns 16 tea estates. Out of these, just two are currently fully operational.

That means around 25,000 Duncan employees are in a perilous position.

Superintending Manager of Bagrakote and two other Duncans tea gardens C P Kapoor says it is normal for a garden to face financial crisis occasionally. “I don’t think the deaths are because of malnutrition, rather because the families are not literate and aware and couldn’t provide medical attention in time.”

He also puts the blame for the mess at the workers’ door. “We couldn’t provide wages for a couple of months so workers left. Without a full work force, how do you expect the tea garden to run at capacity?”

Sumanto Guha Thakurta, secretary, Dooars branch, of the Indian Tea Association, says one way to improve the lot of the tea gardens is better marketing of tea. “There has been a sharp rise in production (Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu), but we haven’t been able to tap international markets. The USSR was one of our biggest consumers but, after it disintegrated, they started making their own tea. We also produce some of the most expensive tea in terms of cost of production. Kenya and Sri Lanka don’t have the kind of costs we do.”

Unable to meet exacting international standards, India has lost the European and American markets to Kenya, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and even Bangladesh. Pakistan remains India’s biggest tea market, importing as much as 35 per cent of India’s tea, apart from the Middle East.

A senior Duncans official says tea production costs have risen 60 per cent in five years. “At the same time, prices have been stagnant since 2008. Assam sells at Rs 210 per kg as opposed to our Rs 120 per kg, without the costs we incur,” he says.

Former Tea Board member Mani Kumar Darnel says they have been fighting for a floor rate. “This is the only industry where the manufacturer has no say in the pricing of his product. If there is a basic floor price, there is a minimum amount that tea garden owners would get.”

Anuradha Talwar, former advisor to the Supreme Court commissioner in the matter of Right to Food, also accuses owners of not thinking long term. “For instance, the age of the tea bushes is a major problem. Like the Duncans… they haven’t replanted to a sufficient extent, so the yield of the tea bushes is falling. This naturally makes the industry unprofitable,” she says.

Thakurta of the Indian Tea Association urges the government to take some of their “burden” off to lower costs. “Tea gardens outside don’t have to provide hospitals and schools and housing facilities like us.”

Some of the tea industry’s demands are getting a hearing now due to the coming Assembly elections. Soon after Mamata Banerjee toured the area last month, Duncans Chairman G P Goenka was summoned by the CID over non-payment to workers and alleged starvation deaths.

Tea estate employees form at least 60 per cent of the vote share in North Bengal, which has 42 Assembly constituencies. While the Trinamool won from here in the 2011 Assembly elections, the BJP had made inroads in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls.

The Left Front has been carrying on a movement with 26 trade unions in the region for two years now. Siliguri Mayor and former CPI minister Ashok Bhattacharya says, “There has been so much debate about whether these deaths are actually starvation deaths. The question isn’t whether the deaths are natural or unnatural. The question is that there have been an alarming number of deaths.”

Finance Minister Amit Mitra was repeatedly contacted but didn’t get back. West Bengal Labour Minister Moloy Ghatak said “there are no starvation deaths” while giving the details of the state government’s Rs 100-crore fund for tea gardens. “It covers all tea gardens and not just those shut. The workers will get housing, electricity, water, medical treatment and schooling. The government has decided to provide these benefits now instead of the gardens. We have also started supplying rice for Rs 2 per kg and wheat for Rs 3 per kg.”

Lakhan Santhal, whose wife died a few days ago, at the age of 53, at Bagrakote estate. Their daughter Malo says he hasn’t been the same since mentally (Express Photo by Partha Paul) Lakhan Santhal, whose wife died a few days ago, at the age of 53, at Bagrakote estate. Their daughter Malo says he hasn’t been the same since mentally (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

As per the government, people have passed away due to natural causes — age or disease. One of those was Lakhan Santal’s wife, all of 53.

For a month before her mother’s death, says daughter Malo, there was little to eat at her parents’ home. Malo is married and lives elsewhere. Both Lakhan, 60, and his wife were tea pickers at the Bagrakote plantation. “On the day she died, there was no food at home. Now the panchayat sends us rice, potatoes — enough to get by.”

Lakhan, who Malo says isn’t the same mentally any more, barely mumbles in response to questions. However, he perks up remembering the time of “the white sahib”, 45 years ago, when he joined the plantation. “I was paid one anna a day then. Things were good. We were taken care of.”

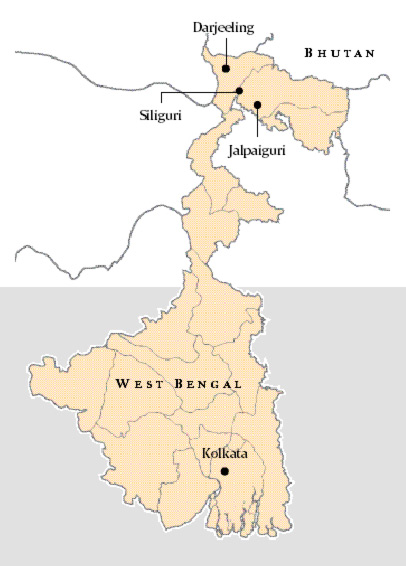

North Bengal, the ‘tea country’

West Bengal’s tea country, North Bengal has three regions where tea is grown — the hill area (in and around the Darjeeling sub-division), the Terai region mainly around the Siliguri sub-division, and the Dooars (covering Jalpaiguri). As many as 277 ‘Set Tea Gardens’ — or organised tea estates — still operate here.

Labour intensive, tea gardens are the second largest employer in India, next only to the Indian Railways. Most of the labourers are descendants of tribals brought as indentured labour by the British, or Nepalese.

The Bengal tea gardens employ 6,03,724 people. While there is no collective figure, an estimated 25,000 are unemployed just across 13 of the gardens run by Duncans.

Between 2002 and 2007, when 17 tea gardens shut down, at least 1,200 deaths were reported in the area.

A survey by the Siliguri Welfare Association last year found the BMI of workers to be 14 in some tea estates. BMI of 18.5 constitutes “famine-affected population”

The workers are entitled to minimum wages of Rs 122.50 per day, ration (rice and wheat), potable water supply, electricity, provident fund payment, pension (after retirement), bonuses, hospitals and schools to be provided for by the management of a tea estate. Umbrellas and aprons are to be supplied for working in the gardens and firewood for cooking.

Findings of a survey by West Bengal’s Labour Directorate of 273 of the Set Tea Gardens:

* In 2011-12, 18,35,55,614 kg of tea was produced in North Bengal

* Only 34 of 81 hill tea estates meet the standard yield there of 500 kg per hectare

* In Terai region, where standard yield should be 1,900 kg per hectare, only 14 of 45 estates meet the standard

* Similarly, in Dooars, where standard yield should be 2,000 kg per hectare, only 40 of 150 tea estates fit the bill

* 84 estates get support from schemes such as MNREGS, and 165 from different banks

* Only 166 estates have hospitals

* 116 have seen a change in management in the past 10 years. “Some are run by promoters who hardly care for long-term development”

* 24 estates in hill areas don’t have irrigation facilities

- See more at: http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/13-years-too-late-for-many-in-north-bengals-tea-gardens/#sthash.f21oRafD.dpuf |